#About Oribe Ware#

Reference: Living National Treasure, Kato Hajime (1900.3.7–1968.9.25), supervised by Koyama Fujio, published by Heibonsha

Oribe ware possesses a unique beauty unlike any other type of Japanese pottery. While Japan has produced many different ceramics, few display such a sense of freedom in design as Oribe ware. To create something new requires both creative spirit and innovation; without them, the result would be lifeless and poor. Oribe ware, however, was born in the Momoyama period—a time that valued individuality—through free creativity and passionate craftsmanship. This is why even today it conveys such a vivid sense of life and dynamism.

How, then, did Oribe ware come into being? According to a well-known theory, during the late Momoyama to early Edo period, Furuta Oribe (1544–1615), a prominent tea master and samurai, and disciple of Sen no Rikyū, commissioned Mino potters to create works that reflected his own aesthetic preferences.

The shapes and designs of Oribe ware are extremely varied and full of change. Its characteristics can largely be divided into “form” and “pattern,” but just as important are the techniques employed. Not only the shapes and patterns, but also the quality of the clay, the methods of construction, and especially the application of glaze all work together with the decoration to produce its distinctive appeal.

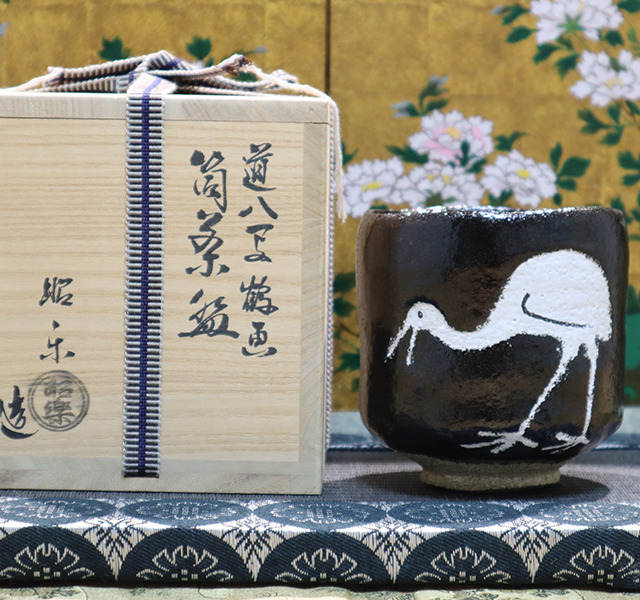

#About Narumi Oribe#

Among its many variations, the type known as “Narumi Oribe” is made by combining red clay and white clay. The white clay sections are covered with a blue glaze, while the red clay parts are decorated with white slip patterns, over which iron lines are drawn. The warm tones of the red clay contrast beautifully with the blue glaze, and this style was often used for hand bowls, square dishes, and “mukōzuke” (side-dish vessels). Some examples include “kutsugata” (clog-shaped) tea bowls, in which only the green portions are joined with white clay and finished on the potter’s wheel, and, more rarely, water jars in the shape of teapots.

This joining technique represents a further development of the “neriage” method seen in Shino ware, and requires great skill. It cannot be achieved with clays that shrink at different rates during firing. It was only thanks to the unique natural clays of this region that such works could be realized.

The photo shows a work by Hayashi Torao, born in Gifu in 1926.

No comments yet.